In 2013, I “discovered” a plainchant Responsory in commemoration of Rudolphus, reno et confessor (see https://youtu.be/BwkH1SAwphY for a recording).

Now, a three-part organum dating from c. 1200 has been unearthed, in a little studied codex from the Notre Dame tradition. It is unlikely that the music is by the Great Perotinus himself, but certain borrowings make it evident that the composer has known the milieu around the Parisian cathedral well.

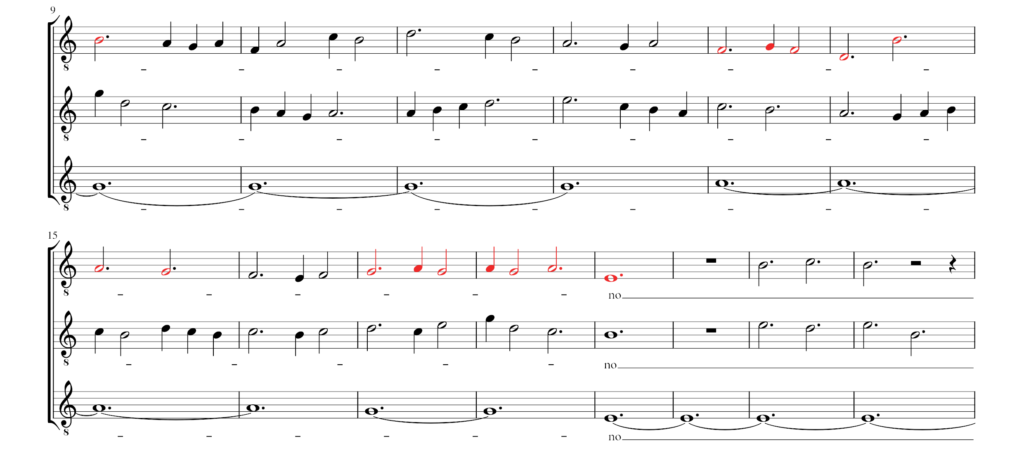

Here is the beginning, in a modern transcription:

The rest of the sheet music can be found here.

Here is a recording by the Capella Grieg:

Some Historical Background

The Organum triplum Reno erat Rudolphus is in the musical style called Notre Dame organum. It flourished around 1200 in the milieu around the newly-built Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. Most famous today are the two organa quadrupla Viderunt omnes and Sederunt principes by the great Perotin.

There has been polyphonic music before his days, but the compositions associated with his name are the first known pieces of music which require a precise notation, since up to four different lines of music have to be coordinated.

Modal rhythm

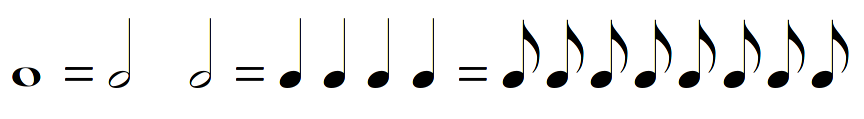

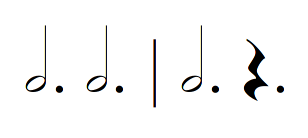

The notation that was used has been called modal. Where modern notation uses separate symbols to distinguish between different rhythmic values:

modal rhythm indicates rhythms through different groupings of identical symbols:

The sequence of notes is the same, and every note is represented by the same symbol, a square note. The only difference is the groups: in the first example: 3+2+2, giving a long-short pattern; in the second, 2+2+2, which gives the opposite pattern; and in the third, 1+3+3, resulting in the more complex dactylic pattern long-short-short(-but-not-as-short) in the last example.

This is also the mode that is used in the beginning both of Reno erat Rudolphus and of Sederunt Principes. A change to the first mode (long–short) occurs in both compositions after a while.

One may notice that all the patterns are in triple time, and that the last note of each group is long, the others short.

The Song Structure

Notre Dame organum is liturgical music – an embellishment of a plainchant song. Both Reno and Sederunt are Responsories, which means that the whole choir sings the “refrain”, while a soloist sings the verses (usually just a single verse). It is also customary for the soloist to intone the whole song.

This gives the following structure:

| Intonation | Respond | Verse | Respond (end) | |

| Solo | Reno erat… | Sanctus Nicholas etc. | ||

| Choir | … Rudolphus, nasum rubrum etc. | Omnes tarandri etc. |

To this you might object: isn’t it the other way around? Clearly, “Reno erat” is sung by the choir, and the continuation with Rudolphus is just a simple melody sung in unison?

That is correct, but not conforming with reality in Notre Dame c. 1200. Words mean different things at different times. The choir is the full choir of monks, singing praise here on earth, as a reflection and a preview of the eternal praise in the chorus angelorum in Heaven. They sing plainchant in unison, as they have always done, day out and day in.

The solo parts are a bit more tricky: why would one think of the passages for three- or four-part choir as solo parts?

Then as now, not all feasts are equal. A plain Tuesday mass in September would not have been celebrated with the same pomp as the Mass on Christmas Day. In Notre Dame this meant: more singers, more priests, more liturgical elements, more solemn melodies, more elaborate decorations – and more soloists. This may seem strange, but on the greatest feast-days, the “soloist” part was in fact sung by a group of six singers.

These were also the feasts where the elaborate music of Perotin was sung – by the solo group. Three of them would have sung the static part, which is actually the beginning of the plainchant melody, and three would have sung the three embellishing parts.

Motet Style

In the first solo section, the intonation, the notes of the original melody are drawn out in the extreme: the first note of Sederunt lasts one minute in the recording above, and the first word three minutes.

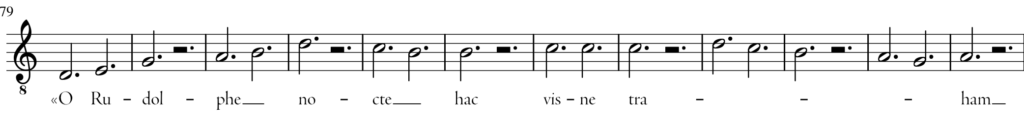

For the second solo section, things are usually speeded up a little. A common technique is to split up the plainchant melody mechanically into chunks with a fixed rhythmic pattern. In Reno, this pattern is the simple

The passage at “O Rudolphe” then becomes:

So there you have it: the bottom part is the “old” plainchant melody (i.e. the one from 2013), the upper parts are embellishments of this melody, according to the pattern established by Perotin, with some stylistic and even melodic borrowings.

It seems that the transition from plainchant style to Notre Dame style, certain melodic traits are emphasised, that may have been latent in the plainchant melody, but which in the new environment bear some resemblance with melodies of a much later date. Some of these similarities have been marked in red and green in the sheet music that accompanies the video.