I’ve earlier performed a little test, comparing two files: one produced with MS Word, the other with OpenOffice.org Writer. The purpose then was to demonstrate that Word isn’t necessarily such a bad piece of software — it’s just not always used in a way which is likely to give nice results: most people don’t change the default settings of Times New Roman/Arial and ragged right margin, and they apply formatting manually for each new element, which is bound to lead to inconsistencies.

Now it’s time for the next round of tests, this time including another application in the comparison: the “typesetting environment” LaTeX. I will also go more in detail with the points of comparison, not just considering the crude parameters such as font size and page margins, but also taking into account the finer typographical details. In the former test, I had deliberately turned off hyphenation. That led to a discussion about various hyphenation algorithms, and this time, I have decided to turn on automatic hyphenation in all three programs, using the default settings.

The contestants

MS Word probably needs no presentation: the omnipresent causer of headaches over lost or corrupted files; the producer of hoardes of ~WRL2354.TMP files in some hidden system directory (look in C:\Documents and Settings\<User Name>\Application Data\MicrosoftOffice if you don’t believe me); and the single most influential spreader of bad typographical taste in a hundred years, since the previous low point in the late nineteenth century.

OpenOffice.org is the flagship of the open source movement: a free equivalent to Word, which boasts an almost perfect and seamless conversion filter, so that you can edit almost any word file interchangeably in Word and Writer without ever noticing. Oh yes, and it’s free, both as in beer — you don’t pay for it — and as in speech — the source code is open, the file format is open, so you don’t need a particular program to view its files (there are at least three word processors which natively use the same file format, and countless others which can read it).

Both of the “W” programs are so called Word Processors. Some hold that the use of the same word in “Word Processor” and “Food Processor” is no coincidence, and anyone who has been met by a screenful of random characters from a ruined Word file will be likely to agree. They are both parts of huge pieces of software, “Office Suites”, with several integrated applications in addition to the word processor: a spreadsheet program, a presentation program, a drawing program, a database application, etc. The principle is WYSIWYG — “what you see is what you get”. You type a “b”, select bold/italic, and that’s what you see on the screen and on the paper you eventually print out.

LaTeX is a different beast: it is a “typesetting environment” rather than a word processor. First of all, there is no icon on you desktop saying “LaTeX” which you can click on to bring up the LaTeX program. There is no one particular “LaTeX editor” — any editor which can open and save plain text files without messing them up by adding Microsoft’s secret codes at the end, can be used. Already this is a concept which is foreign to most people who have gotten used to the modern point-and-click way of doing things. (True story: most of the people I have sent LaTeX files to, have complained that they could not open them. Here’s lesson #1 today: just because Windows doesn’t automatically know which program to use, doesn’t mean that there is no program to use).

Edit: Judging from the many comments I’ve received about this parenthesis — most of them along the lines of “What kind of an idiot sends LaTeX files to ordinary people?!?” — I think a clarification is in place. I’m referring to a handful of occasions when I’ve needed an author to check some little detail, or a proof-reader to go through a text. I’ve sent them the files — accompanied with PDF files — along with instructions to disregard all the \command{this} and \environment{that} rubble. I don’t expect them to install some tex variant and process the file, just to be able to open it, since it’s simply a plain text file. These are people who think that word files live in Word and that it must be the same way for all other kinds of files too.

In fact, LaTeX is much closer to being a “Text Processor” than the other two, it just does the processing much better: You feed it some raw materials, and out comes, not scrambled eggs, but a whole pie complete with chicken and cheese, pefectly seasoned and baked precisely long enough to give it a nice crispy surface without getting burned.

It fills the outer limits of the area where word processors occupy the middle ground. The “raw material” in this case is text which looks like this:

\noindent\lettrine{I}{t is easy} to be seduced by Dylan's lyrics:

\textit{they} were essential when he was nominated for `Voice of a

Generation', and \textit{they} stuck in the fans' throats when he converted

It may look cumbersome, and it is, but the reward comes when you process it and print it out. It then becomes clear why it’s called a typesetting environment: LaTeX is in fact a tiny little typographer, trained by Gutenberg (he’s very old now) and still upholding the craft with pride. A Word document may look nice on the screen, but no publisher with any self-respect would ever publish a book directly from a word file.

The document

Layout in Word, Writer, and LaTeX (pdf file)

For the test, I have used two pages from an upcoming chapter from Things Twice — the book. I have tried to the best of my ability to use exactly the same layout in all three programs. In theory, this is just a matter of writing down settings in one place and applying them in the other, but in practice, it is slightly more involved. In Word, the header and footer are not considered to be part of the page area: if you want the header to start 3 cm down on the page, you will have to indicate a 4 cm upper margin and a 1 cm header, which is a strange way of dealing with the page layout parameters, and one which can cause quite a lot of frustration and trial and error. But those problems aside, I have used a page area of 12x18cm, a font size of 11.5/13.2pt (i.e. 1.7pt leading), a three-line drop cap for the first paragraph, and a slightly stylish, book-type of chapter heading. The font is Adobe’s Garamond, the most beautiful font in the world.

The pdf file contains the following four versions:

- MS Word

- OOo Writer, produced under Windows.

- OOo Writer, produced under Linux.

- LaTeX, produced with tetex, under Linux.

So how do our contestants fare?

At first sight, all the versions seem pretty equal, which should not be surprising, since all the brute settings are the same. The page number on the front page is a little lower in the Word Processors, but that’s because of an oversight on my part, not because of intervention from the programs.

But let’s look a little closer.

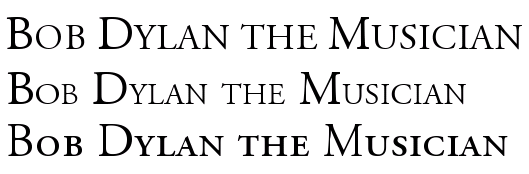

Small caps

The first major difference appears in the subtitle. It is set in small caps. Small caps are a separate set of characters where the lower-case letters have the same shape as the upper-case, but the same size as ordinary lower-case letters. Most fonts don’t contain any small caps. If they exist for the font in question, they are usually supplied in a separate font file, but neither Word nor Writer can handle them directly. Instead, they take the capital letters and scale them down. This may seem like a good idea: why double the work? but there are some problems, which the W/W versions show.

There is no fixed proportion between upper- and lower-case letters. Some fonts have high ascenders (the long lines in letters like “k”, “l” or “M”) and a small “x-height” (the height of — you guessed it — a lower-case “x”); others may have shorter ascenders and bigger “x”s. But a word-processor has to make some choice, and Word has chosen to let the lower-case small caps be 80% of the upper-case letters, whereas Writer uses c. 66%.

Figure 1: Small caps in Word, Writer, and LaTeX

In this particular font (Adobe Garamond), the ratio between upper- and lower-case small caps is almost exactly the same as in Writer, and one would think that Writer’s version would therefore look good, but it doesn’t. Why? Well, all letters in a font are designed to look good at their correct size, next to their neighbouring characters, but when they lose one third, the lines become way too thin. They stand out as the only element on the whole page with a different “colour”, the typographical term for how the ink is distributed on the page. It is apparent in the subtitle, but it becomes even more painful in the first couple of words, where the fake small-caps look like starved post-war kids next to the healthy regular letters.

Word’s solution is slightly better, but it has its own problems. First, the difference between upper- and lower-case letters is so small it is almost negligible. And secondly, together with regular text, the lower-case substitutes become much too big. This may be a minor problem since their function is to stand out from the rest, but the combination “too tall and yet so skinny” is forgivable in a teenager but not in a full-grown office application.

Now turn to LaTeX, which uses the characters which are designed specifically as small-caps. Notice the color: it’s the same as the rest of the text. There is a clear difference between upper and lower case, and although the letters are about the same height as Writer’s “small-caps”, they look infinitely much better, because the lines haven’t lost a third of their weight.

Latex: 3, Word: 2, Writer: 1

Numerals

While we’re on the subject of letter shapes: a proper font should contain proper numerals, but most don’t, at least not in places where simple programs like Word can find them. The number shapes in the two Word processor files are fine for tables, phone books, and math exams, but they are not designed to be part of a running text.

What you will find in a book like this, is the shapes in the LaTeX version. This is not because the LaTeX font is different from the one W&W use (in this respect; in many other respects it is), but because Latex knows where they are and you can order it to use them. W&W only knows about one set, and uses that. (In the Writer-Linux version, I have used a version of the font where I have moved the nice typographical characters to the place where tabular ones, which I will never want to use, are usually found.)

Latex: 3, W&W: 1

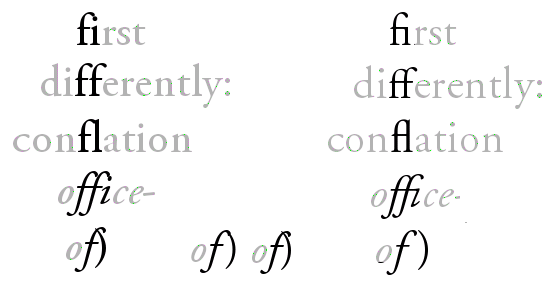

Ligatures

But wait: there’s more. Some letter combinations are more difficult than others. The letter “f” is particularly troublesome, and therefore, there’s a long tradition — back to Gutenberg, actually — of making special characters for the combinations “fi” “fl” and “ff” (and “ffi” and “ffl”) — so called ligatures. Most fonts actually have these, but again, W&W doesn’t use them. This is a consequence of the WYSIWYG paradigm: in order to produce the same output on screen as in the finished file, the word processor will have to change two characters — “f” and “f” — into one — the “ff” ligature — on the fly, and be ready to change that again into the three-character ligature “ffi” if the next input is an “i”. With today’s processing power, this should not be a problem, but when these programs were born, this would have slowed down the process too much, and a 600-year long tradition of typographical cleanliness was thrown out the window (example; left side).

Figure 2: Ligatures in Word (left) and LaTeX (right)

For LaTeX (right side), this is no problem, since the input and the output are two different processes. With all the visual pollution in today’s printing world, it may seem a small thing, but once one has gotten used to seeing niceties like the italicized “ffi” in “office”, one cringes when one sees the crash site that W&W can sometimes produce.

And while we’re on the topic of crashes: have a look at the last example: italicized “of” followed by an upright parenthesis: of). It is almost bound to create a mess. Word certainly does, with the linux version of Writer close behind. Strangely, the Windowpeoples version has a better solution, but still with a clash. Again, LaTeX is the winner, with a clear separation between the characters.

EDIT: It has been suggested to me that MS Office 2007 has the option to enable typographical numerals and the ligatures if the font provides them. When the article was written, I didn’t have access to the new beast from Microsoft. Now I have, and if this is in fact featured, I haven’t been able to find out how. A default document still prints out like in the images above.

“Badness”: laying out lines and paragraphs

These are all nice details having to do with how to deal with characters. But the greatest difference between the two word processors and LaTeX, is in the area of paragraph and line formatting. Most word processors adjust the inter-word space line by line, by filling up each line as much as possible. But what if the next line ends with some indivisible, long words? In that case, the line-by-line approach becomes doubly bad: the second line will have big holes — bigger than necessary, even — and the contrast between an overstuffed line and a Swiss cheese line is a death-blow to even page colour.

LaTeX takes a different approach. Instead of fixing the lines, which are just random segments of text, the whole paragraph is considered, and if a problem at the end of the paragraph can be solved by dividing a word differently in the beginning, then that’s what will happen. This prevents the problem with one tight line followed by a loose.

There are some examples of this in the example text. None of them are catastrophic, but at least they illustrate the problem. In the second paragraph, W&W hyphenate “atten-tion”, cramming as much of the word as possible into the first line. But at the end of the next line, there is the word “meaningfully”, which cannot meaningfully be split so that any part of it will fit on the second line, which must end with “cannot”, leaving a number of holes in the line. LaTeX, having looked at the whole paragraph before making a decision, knows this, and divides “at-tention”, in order to distribute the extra space more evenly.

The same is the case in the next paragraph, where there would have been room for the whole “performance” on the third line, as Word has done, but that again gives holes, which LaTeX avoids by dividing “perform-ance”. Writer has somehow managed to get one more word into the fourth line, but there are lines with holes later on in this long paragraph, and they may have been caused by the zealous space-saving earlier.

In LaTeX jargon, this is called “badness”. If LaTeX comes across a paragraph which it cannot divide in any good way, it will give a warning, in effect saying: “as the text now stands, this is impossible to make nice. Do something! Rewrite!”. This is a tremendous advantage: when one has compiled a document, one gets a list of the places where there are “badnesses”, which one can then correct manually. I have edited books of 3–400 pages, and the ability at a glance to review all the dubious places is a time-saving miracle — on top of the comfort of knowing, when all is corrected, that you (i.e. LaTeX) haven’t overlooked anything.

Hyphenation

Hyphenation is a necessary evil: it maintains the flow of the line at the cost of breaking a word in two. There is also the danger of splitting at wrong places, because hyphenation does not always follow strict rules.

The hyphenation points chosen by the three programs are all ok, as far as I can judge. Word has followed the American practice of disregarding the original meaning of compound words, giving beauties like “bi-ography” in the last paragraph, and also the horrible “danc-ing” on the middle of that page. But both are allowed, so that’s ok.

LaTeX has been instructed to follow the British English rules, and so we get “perform-ance” instead of “perfor-mance” on the first page. The only dubious decision is “signific-ation”, which according to Merriam-Webster (with US rules) should be “sig-ni-fi-ca-tion” and according to Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary “sig-nif-ica-tion”. So we actually have an error… The explanation may be that the other “signific-” words, “significant” and “signification”, split after the “c”.

Writer follows LaTeX concerning “signification”, but other than that has unproblematic decisions.

“Uncials”/Drop caps

The first paragraph begins with a drop-cap, an initial covering three lines. All three programs do it slightly differently.

Writer’s “I” is too big; it breaks the square of the text area. Word’s is better: the top of the “I” aligns with the height of the ascenders, which is acceptable.

One thing to keep in mind concerning drop-caps is that the magnification of the letter also means that the space around it grows, and with some letters, this may call for some manual adjustment of the position of the letter, so that it will look right instead of being mathematically right. An “O” will look smaller than it is; “A” and “W” have limbs sticking out in various directions, which may trick the eye, and so forth. In other words: there must be an option to fine-tune the size and position of the initial letter. Both Writer and Word give you the option to adjust the space between the letter and the rest of the text, but nothing more than that. LaTeX, on the other hand, lets you configure everything. In this example, I have increased the size of the “I” by a fraction — mainly because I could…

Points and space

I have to confess: I have cheated — on one point. The ellipsis points at the end of the first paragraph — they didn’t have to end up being separated from the “cetera” to which they belong. I could have inserted a hard space between the word and the dots, but I didn’t, for two reasons. One is that most people don’t: either they type word–space–three dots, which the program may or may not replace with the “ellipsis” character (consisting of three dots, but as a single character), or they insert the ellipsis character themselves — after a space. And the result may be as in the W&W versions.

The other reason is to get a chance to illustrate one further point: regardless of how one deals with the ellipsis in the word processors, it will stand out, some way or another. Use three dots, and they will come too close together. Separate them with a space, and they will come too far apart. Use the single-character ellipsis, and things are slightly better, but the three dots are still closer together than the surrounding spaces. This will only get worse if there are extra holes in the line owing to bad paragraph justification.

The LaTeX dots remedy all these problems, because they neither use a fixed character, nor dot-space-dot-space-dot, but something in-between: single dots, separated by a fixed space, less than a full space. In this case, I have even adjusted the space to my liking, both between the dots and the distance to the previous word.

The same can be said about the troublesome title of the Hymn of a Generation, ‘The Times They Are A-Changin” with the two apostrophes in a row. It’s bound to be ugly whichever way one treats it, but one can get decent results. For the LaTeX version, I have used a 1pt space. I could have done something similar in the other versions, but I didn’t, again because it’s not what the default user — or even the advanced user — would do. I’ve used a normal space, which is too much.

Verdict

Time to sum up the evidence. I think I stopped handing out point at some point, but that doesn’t matter: I can form a verdict without them.

If the visual output is the decisive criterion, there really is no competition: LaTeX wins on all counts. Word and Writer follow on a respectful distance: they both fulfill the most basic tasks reasonably well, but fail flat out on others. Word has a slight edge because of the nicer small caps and the drop-cap, but the difference between Word and Writer are negligible; and on other points, such as the italicized-f-plus-end-parenthesis, Writer wins, so let’s call it a tie.

This short example has of course only scratched the surface of what the three applications can do. Because of the integration with the other elements in the office suits, Word and Writer can handle embedded spreadsheets, drawings and diagrams, and similar effects, and including images is very easy, but once you try to place them where you want them on the page, the result tends to be horrible. LaTeX is the industry standard for mathematical formulae, places images where they should be, and can do just about anything with a paragraph (try to make a justified paragraph with the last line centered in Word…). All in all, it is probably fair to say that there are few limits to what you can do in any of the three alternatives if you know them well, but LaTeX always produces the best results.

Another strength of LaTeX lies in the handling of large documents, where the separation of editing and processing can be a lifesaver. I’ve had 400-page documents crash in Words more times than I care to remember, and the final stage of producing such a book is a desert journey on the verge of a nervous breakdown both for the author and the computer. Not so with LaTeX: no matter how long the text is, since it’s “only” plain text, and all the heavy formatting lies outside of the document, the concrete interaction with the text is always unproblematic. Behind the scenes, the same paragraph for which I gave the LaTeX code initially, looks like this in Writer:

<text:h text:style-name="ChapterNumber" text:outline-level="1">Chapter 10</text:h><text:h text:style-name="ArticleTitle" text:outline-level="3">The Uneven Heart</text:h><text:p text:style-name="ArticleSubtitle">Bob Dylan the Musician</text:p><text:p text:style-name="Standard"/><text:p text:style-name="Standard"/><text:p text:style-name="BodyTextDropCap">I<text:span text:style-name="T1">t is easy</text:span> to be seduced by Dylan’s lyrics: <text:span text:style-name="T2">they </text:span>were essential when he was nominated for ‘Voice of a Generation’, and <text:span text:style-name="T2">they</text:span> stuck in the fans’ throats when he converted to Christianity. Equally easy is it to question his musical abilities: ‘He can’t sing’, ‘he can’t play the harmonica’, ‘he only knows three guitar chords’, ‘his lyrics are good, but I can’t stand the voice’. Et cetera <text:span text:style-name="T3">… et cetera …</text:span></text:p>

Since the program has to deal with all that, constantly, a long document can become a huge workload.

That said, writing in LaTeX isn’t a bed of roses. It can be a hassle to get anything other than text into the document; looking at the extra code all the time is a nuisance; setting up the basic document properties, which is done with a couple of clicks in W&W, can be a long process with a manual in your lap; there is ample room for error to sneak into the code (and it is code; writing in LaTeX is a kind of programming).

For anything but short memos, all this is outweighed by the beauty of the final result. But this isn’t even the main reason why working with LaTeX is such a thrill. It has to do with control, with the difference between having a program which invites you do what you want, and one which you must frequenly fight to make it yield to your wishes if you wish anything which goes beyond the defaults. It is easy to produce good results in Word, but it’s hard to produce anything that’s better than good. In LaTeX, it’s the other way around: it’s cumbersome to get even to the default result, but once you’re there, it’s great, and from there to the truly magnificent specimens of typography it’s just a series of small steps.

It’s not having defaults that’s the problem with Word — in fact, LaTeX is nothing but a huge set of finely tuned defaults — it’s the assumption that you are and should be happy with that. It’s the difference between empowering you and crippling you.

Leave a Reply