Or: To Live Outside The Law, You Must Be Honest

Here we go again: Dylan has nicked a song from an old, forgotten musician, and the apologists flock around him in his defence. This time it’s False Prophet from his recent album Rough and Rowdy Ways that has been found to be remarkably similar to If Lovin’ Is Believin’, an obscure B-side from a Sun Records single from 1954, recorded by Billy “The Kid” Emerson, who is perhaps vaguely remembered by a handful of early R&B nerds for some other single from the same year, but otherwise completely forgotten (although still alive, and now known as Reverend William Emerson).

Here’s what the defending army say (this and this article sum up the arguments quite nicely, the following is a condensed list):

– It’s the folk tradition!

– Thank god there were no copyright laws when Shakespeare was around!

– Dylan’s changes to False Prophet may be small but they are significant, so it’s not really plagiarism.

– Dylan is doing the original creators a favour. If he hadn’t stolen their songs, nobody would have listened to them anyway.

– He may have borrowed a tune here and there, but it’s not done with any ill intent, so at least it isn’t plagiarism.

– There are only so many notes out there; similarities are bound to appear.

– Besides, who knows, maybe Dylan has settled this privately with the originator; then everything is handy dandy, right? Right!

– He may have nicked the arrangement, but arrangements can’t be copyrighted.

– Copyright didn’t apply legally before 1989 if the copyright symbol wasn’t attached; maybe the original authors had forgotten the little ©?

Wussies and Pussies

These allegations, that are more or less related to the contents of the songs and the intentions behind, are frequently accompanied with an “inverse moral indignation” on the part of those who feel hurt by criticism of Dylan:

– The mean detractors are always looking for ways to put Dylan down.

Dylan himself has come out strongly with this argument, stating, when asked about the accusations of plagiarism:

Oh, yeah, in folk and jazz, quotation is a rich and enriching tradition. That certainly is true. It’s true for everybody, but me. There are different rules for me.

Wussies and pussies complain about that stuff.

From Mikal Gilmore’s Rolling Stone interview Bob Dylan Unleashed (2012)

To which there is really only one thing to say: Boo hoo, Bob! Yeah, you’re being so unfairly treated. No go cry on someone else’s nanny’s shoulder.

But for the rest: Do these arguments redeem him, and if so, and perhaps more importantly: of what? What are the charges? What are the issues, what is at stake here?

In this text, I would like to (a) briefly summarize the issues; (b) go through some of the evidence that is frequently cited, on either side, whenever Dylan’s alleged plagiarism is discussed; and (c) suggest two test questions that may help to decided whether and why (or why not) it matters that Dylan steals.

I should mention that without this text I probably wouldn’t have written the following; I hope I haven’t stolen too much from it. I don’t think so.)

The Charges

The accusations mainly fall into two categories: one having to do with copyright and the legal issues surrounding it; the other more vaguely connected with questions of what is wrong and right, justifiable or damning. In both cases one could argue that matters are very clear, but also that they aren’t, and that whatever clarity a decision on those particular issues may bring, may not even matter. What’s important with False Prophet can probably not be reduced to a legal or moral matter. This is after all human communication, art, stylized emotions we’re talking about here – emotions stylized in sound, at that: in the medium where language takes place, but without the added burden of conceptual thought.

Put simply: what Dylan is doing on False Prophet may be important, but whether or not there is a paragraph in a law book somewhere that may send him to jail (or a commandment to send him to Hell) is of no importance for this question.

Copyright Law

In a way, copyright law is real simple: if you’ve produced something, it’s yours to sell, even if it is not a material thing. If you carve a flute out of a marble block, it’s yours; you can play on it as much as you want. What copyright adds is that if you come up with a great melody while playing, that tune is also yours, and nobody can copy it and claim it as theirs. You have the “copy-right”.

So far, it’s simple, but that’s also where “simple” ends. There are two major obstacles: if it’s not a physical thing but some intangible activity that is being copied, how is one to determine what that object is and where the limits are of what constitutes copying? And: what does it really amount to, this right of yours? Who is going to protect it, and under what circumstances? And against what?

Is it the principle of a hole through a piece of marble, the finger holes, the shape of the tailpiece, the particular sound it makes, the size, the colour that determines your flute? How identical must my flute be to yours before you can start complaining?

The comparison with the marble flute even highlights one of the serious problems with copyright protection: it really only applies to ideas or realizations of ideas, not to actual things. If I see your marble flute and copy it, it is not my flute that would be an infringement; only if I sell it, for example under circumstances where you had made a name for yourself as the Carver of Flutes and I somehow made money not primarily from carving my own flutes, but from your idea. The equivalent to a copyright infringement would be if I simply stole your flute and sold it. Copyright law is about protecting ideas as if they were physical objects; and about protecting your right to make money from your formulation of an idea (but not your right to the idea itself).

Fundamentally, the idea of copyright presupposes a society where doing something that does not put food on the table or produces something tangible, such as a marble flute, is still valued, which is a quite advanced idea. But since it is more difficult to define an idea than a flute, copyright law is a mess. And since it’s mostly about the right to make a money from non-tangible activities, it also comes in touch with other areas of money-making, including corruption, exploitation, abuse, etc. Money doesn’t talk, it swears, you know.

It is worth noticing, for example, how the goal of copyright is defined in US law:

To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

Yes, it is We, The People who shall benefit from the protection (for Limited Times, mind you) of your right to your Writing, since it may turn out to be a “useful Art”.

That’s fair and good; it is your choice not to till the earth but write poetry instead, and if you can make people pay for your bread, then all the power to you. But why is it then, for example, that copyright protection does not end when you die but usually lasts until you’ve been dead for 70 years? If you’re not there to eat the bread your poem has earned you, then what right is there to protect? Could it be that a law that was made to ensure you the right to earn your living from something useless, because we as a society feel that we benefit from that, is instead being used by parties with economic interests of their own, such as publishers, licencees, lawyers, etc., to secure a long-term, effortless income?

Yes. Copyright law aims to fulfill an aim that is good both for society and the individual – the right to improve society without necessarily putting a bucket of grain or a marble flute on the table to prove your worth – but since the object that is protected is both intangible and vague, and since the area in which it is protected is a commercial one, it is inevitable that there is a gray zone that can be exploited.

So one question is: is this what Dylan is doing here, and has been doing since the start of the millennium? Many of the questions that I summarized initially fall into this category: either: copyright law doesn’t cover precisely what (whatever) it is that Dylan has done – be it a missing ©, a shady deal behind the stage, or some other loophole having to do with definitions and intentions (is it plagiarism if your intentions are good? or if you do it openly?). In any case: since we can’t put a paragraph behind the accusation, what he is up to must be ok – how else can we judge it?

Common Decency

The other cluster of objections has to do with morals: it is wrong of Dylan to do what he has done, whether or not it is legal.

I happen to fall into this category myself: I think it’s a disgrace for one of the greatest creative minds of the past century to sink so low – and to consciously and consistently do so – that he can’t even bring himself to recognizing his debt to those who have gone before him. At the time he released Modern Times, it might have been written off as a faulx pas, but not anymore: it’s a consistent modus operandi, and that’s not OK.

But here’s my problem: I can’t really anchor my position securely anywhere. The law is problematic since it mainly protects things that I’m skeptical of in the first place (such as the right of crooked corporations to claim ownership of expressions of ideas that should belong to mankind), and morals are at least disputable and in any case hard to define.

I therefore need firmer ground. Hence the following discussion of some items that have been brought up in the discussion – this one, and those that have taken place before – whenever Dylan’s thievery comes up.

Exhibit A: Blowin’ in the Wind is based on No More Auction Block

One of the cases that curiously enough is always brought up in these situations, is the roots of Blowin’ in the Wind in the old spiritual No More Auction Block (again closely related to We Shall Overcome).

It is curious for several reasons: the influence has never been denied, it has always been described as a point of departure, an inspiration, but hardly more than that, and the similarities really aren’t that substantial.

This ought to have made it an irrelevant argument, on either side, but since it is constantly referred to, let’s get the facts straight:

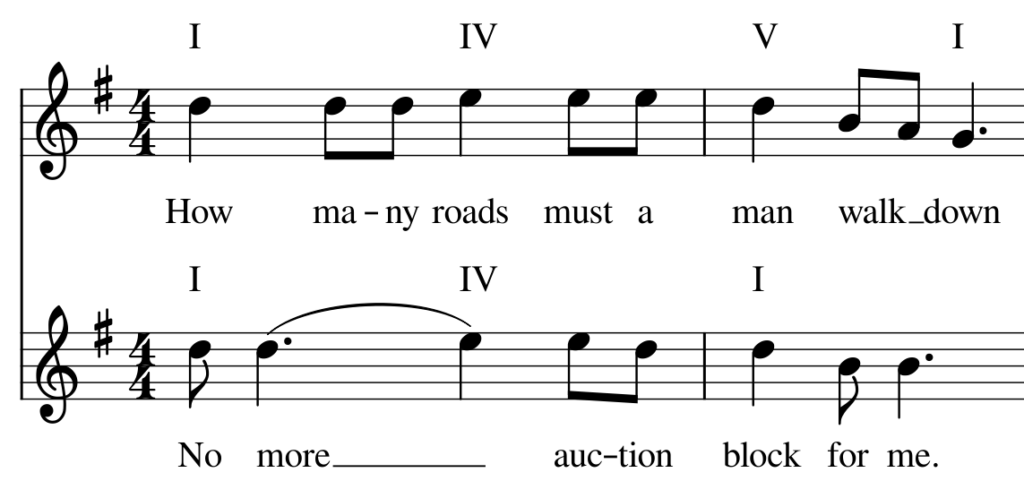

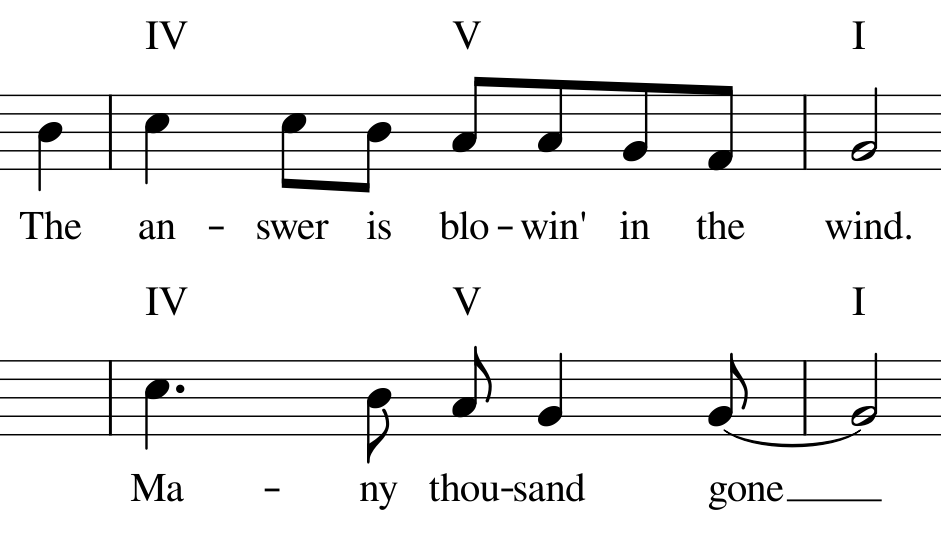

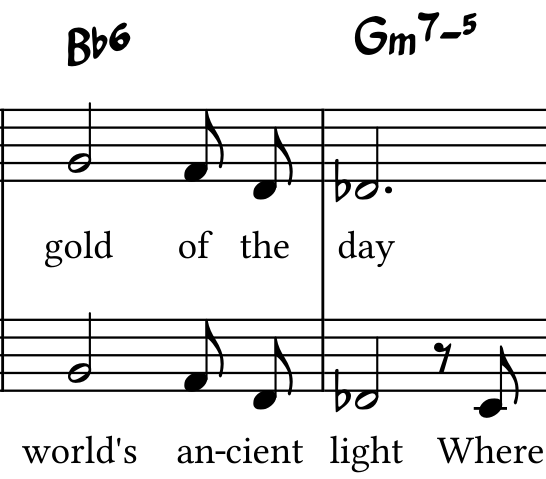

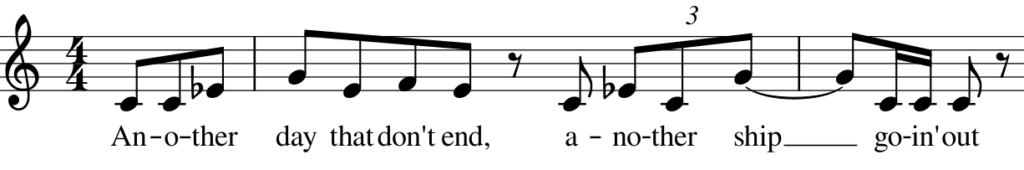

The similarities between the two songs are obvious but limited. The beginning is identical, when it comes to the melody, the harmonization (the album version differs slightly, but most live versions use the same harmonization as on No More Auction Block), and the phrasing:

And the end is equally similar:

Nobody would dispute this, and nobody has. Pete Seeger pointed out the similarity and the origin, as reported in John Bauldies liner notes to Bootleg Series 1–3 where Dylan’s recording of No More Auction Block was released, and Dylan himself said so:

Blowin’ in the Wind’ has always been a spiritual. I took it off a song called ‘No More Auction Block’ – that’s a spiritual and ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ follows the same feeling.

Should further evidence be needed in Dylan’s defense, one might point out that the loan is limited to the first and last phrase and to the overall mood of a spiritual – “the same feeling”; and that the rest of the song structure is very different: Auction Block is a stylized call-and-response type of song, where one phrase is sung and then repeated in a slightly varied form:

I IV I iv V No more auction block for me, no more, no more I IV I vi IV V I No more auction block for me, many thousand gone.

Blowin’ is a ballad with a longer verse structure with a certain harmonic pattern, ending with a clear refrain:

I IV V I

How many roads must a man walk down

I IV I

Before you call him a man?

I IV V I

Yes, 'n' how many seas must a white dove sail

I IV V

Before she sleeps in the sand?

I IV V I

Yes, 'n' how many times must the cannon balls fly

I IV I

Before they're forever banned?

IV V I IV

The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind,

IV V I

The answer is blowin' in the wind.

So on a scale from complete independence (0), through influence (1), similarity (2), striking similarity (3), identity (4) to theft/plagiarism (5), and with a second axis going from open to covert and a third from innocent to crooked, this one obviously scores a clear 2 on the first axis and zeroes on the other axes: Blowing in the Wind is influenced by and therefore shows some similarity with Auction Block, but it is an open loan and morally white as a dove.

And the lesson to be learned from Exhibit A is that even melodic identity may have to be evaluated in terms of the larger context (in this case: the song structure) before a verdict can be passed.

Exhibit B: Dignity

Equally easily dealt with is the accusation that Dylan stole Dignity from James Damiano’s Steel Guitars. I’ve written exensively about it before (including a blatantly plagiarized song of my own), so let’s just say: the accusation might have been substantial had there been any similarity between the two songs, but there isn’t, so it isn’t. And there aren’t either any lessons to be learned, other than: don’t believe everything you read on the internet (and, Bob: next time James brings charges against you: call me!)

Exhibit C: Canadee-I-O and Arthur McBride

This one is more tricky, since it introduces the other aspect that in some form or another plays a role in the discussion about Dylan the plagiarist: the moral issue.

Here’s the story (which by the way hasn’t figured in any of the more recent discussions, as far as I have noticed, but it was a hot issue once, and it might show up again):

On the acoustic revival album Good As I Been To You (1992), Dylan released the song Canadee-I-O. The song had recently been recorded by English folksinger Nic Jones, which is also probably where Dylan had learned the song in the first place. Now, Jones had just been in a crippling and career-ending car crash, and when Dylan’s version came out some people claimed that he had stolen Jones’s arrangement without giving credit – the star had taken a poor, bedridden man’s well-deserved money.

Sad as Jones’s story may be, even a cursory comparison reveals that the two versions have little or nothing in common. Jones’ arrangement is a highly sophisticated finger-picking exercise in open tuning, with bends and advanced harmonies; Dylan’s an energetic and straightforward flat-picking. (See this for a more thorough analysis).

A related case is ArthurMcBride on the same album: Dylan had quite obviously learned the song from Paul Brady, the way he also learned Lakes of Pontchartrain, at about the same time. Brady recalls their meeting in a hilarious interview: how Dylan contacted him and asked him: “Hey, this song of yours, Lakes of Pontchartrain, can you teach me how to play it?”:

Brady’s version is, just like Nic Jones’, a very advanced, sophisticated finger-picking arrangement, and Dylan, of course, had no chance. Brady describes how he had to physically place Dylan’s fingers on the fretboard, chord by chord, finger by finger.

Brady’s description reminds me strongly of the painful scene from the recording of We Are the World in 1984, where Stevie Wonder tries to teach Dylan his one line in the song:

Charming, perhaps, but very painful.

Needless to say, what Dylan ended up playing when he eventually did Pontchartrain live, throughout 1988 and 1989, sounded nothing like Brady’s version.

The same goes for the two songs from Good As I Been To You: the songs are of course the same, the chord sequences are the same, but to say that the arrangements are the same, would be to do mssrs. Brady and Jones a huge disfavour: Dylan is not doing what they’re doing, by far.

In sum: on the independence–theft scale, Dylan again scores low, ca. 1.5, with nothing on the other scales. And lesson learned: similarity with one aspect of a source doesn’t count as plagiarism if it’s another aspect that has been borrowed. In both these cases: Jones and Brady had made distinctive arrangements, but the songs were public domain, and it was the songs that Dylan had learned. Learning a song from someone is not plagiarism. Learning a song from someone is a Good Thing.

Exhibit D: Timrod, Ovid, and Saga’s Yakuza

It’s getting hotter: next up is the bulk of literary loans that will also come up every time Dylan opens his mouth, from now until the day he dies. I assume that he must have known that this was going to happen when he started doing his collage work, back around the turn of the century – I even reckon he was playing with it, toying with us, his fans, the Dylanologists and the news-people. I also assume that he has perhaps regretted it once in a while: perhaps the whole thing became bigger and more annoying than he had imagined. In any case, it’s one of the main reasons why “plagiarist” now shows up virtually every time his merits as a poet are discussed.

(I’ve discussed Modern Times and these issues quite thoroughly before, so I will not go into the details here. I refer to the full text for a more thorough argument:)

It is indisputable that Dylan has been playing around with quotations, hidden references, loans, at least since “Love and Theft” in 2001, and in a much more consistent manner than the occasional citations that showed up here and there earlier. Whether he’s mainly pulling our legs in a game of hide-and-seek (as he obviously did in the “mathematical music” passage in Chronicles I, where he worked in entire passages from a text about “how to build a cult following” in a text that is mostly mumbo jumbo and exactly designed to build a cult following) or he is involved in a grand artistic venture involving textual and musical collage – be that as it may; for the issues I’m discussing here, the literary loans are fairly irrelevant.

Yes, the borrowings are indisputable, yes, they are done secretly, without source references, but they are probably not crooked: he has not lifted the lines from Timrod or Saga or Ovidius in order to make his own task easier or to piggyback on greater minds – this would be the most understandable reason for stealing someone else’s work.

On the contrary. He is not simply influenced by Junichi Saga – he has used his exact words, so technically we are in the area between 4 and 5: identity or theft. But the construction that results from his borrowings does not really depend on them – neither on (or for) their quality nor their content.

The reason why a loan/theft from Saga counts as irrelevant whereas the loan/theft from Emerson puts Dylan’s whole artistic project as a musician into question, is the heart of the matter, which brings us to the relevant issues: the musical loans, and what it is that sets False Prophet apart from Blowin’ in the Wind and Masters of War.

Exhibit E: Bing vs. Bob

Seemingly one of the clearest examples of plagiarism on Modern Times is When the Deal Goes Down – crystal clear because Dylan himself had talked about the relationship long before the song was released – albeit not openly, but also not a secret. In 2004, two years before Modern Times came out, journalist David Gates had interviewed Dylan for Newsweek about his autobiography Chronicles. Later, in a live show, Gates answered questions from the Internet. Someone from Martindale, TX asked: “Did Bob share any details with you regarding the songs for his next album? What’s the scoop?”

Gates answered:

Really only that he’s working on them. he did say he’s written a song based on the melody from a Bing Crosby song, Where the Blue of the Night Meets the Gold of the Day. How much it’ll actually sound like that is anybody’s guess.

Newsweek Live Talk, Sept. 2004.

Of course, now we know and don’t have to guess anymore, and the comparison is really quite interesting, both in itself and as a backdrop to the question of False Prophet.

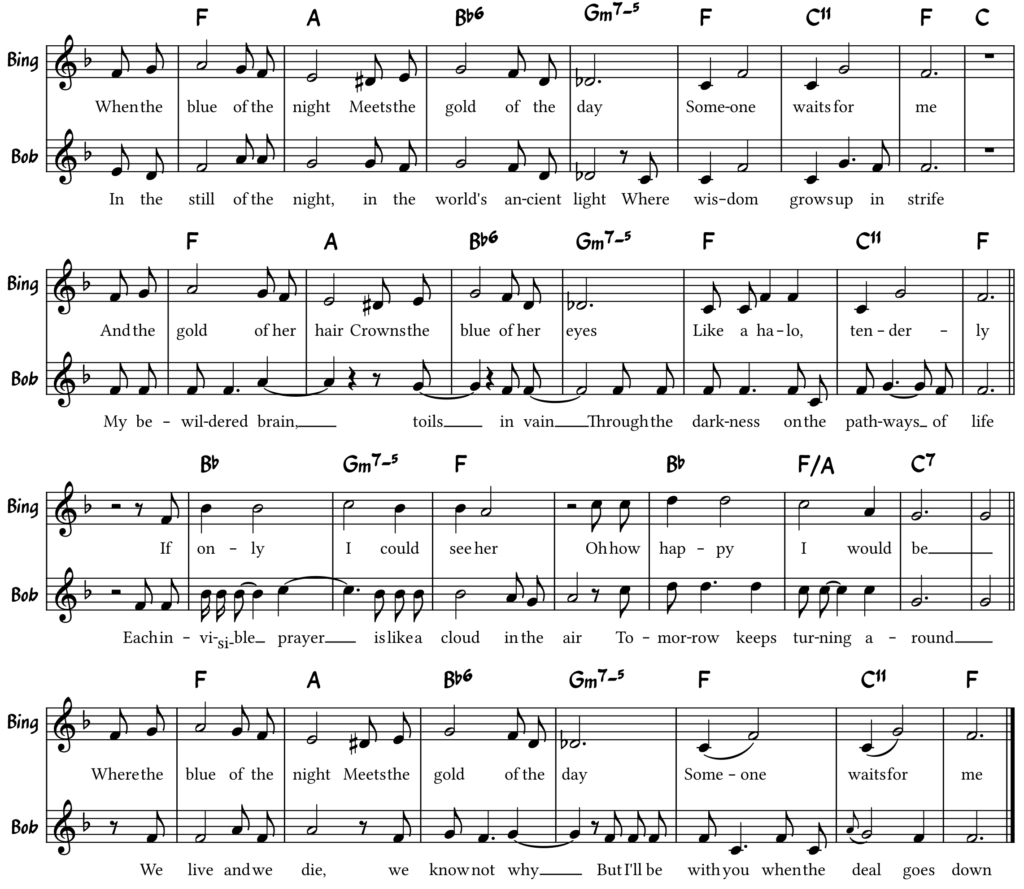

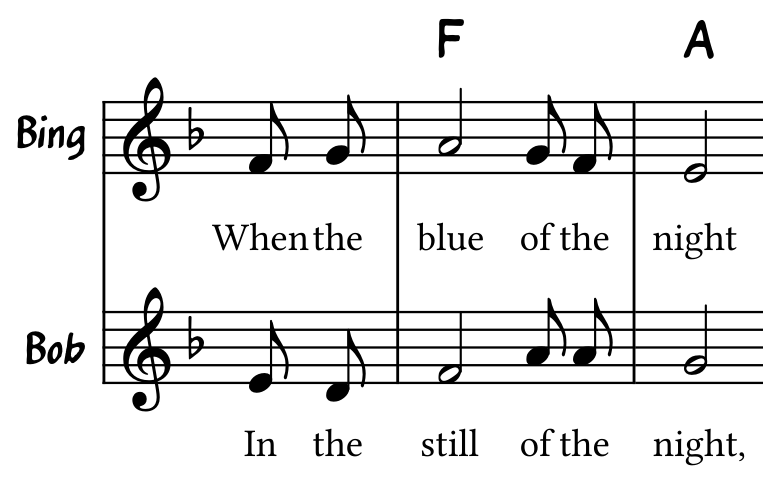

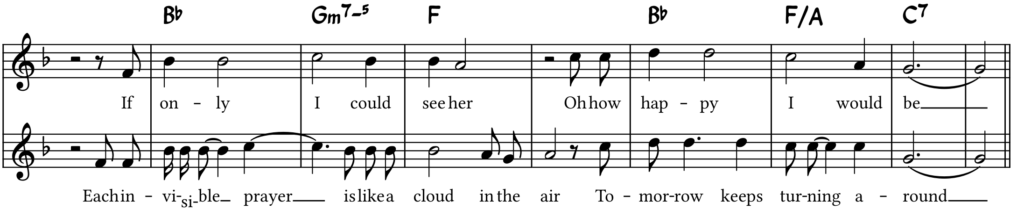

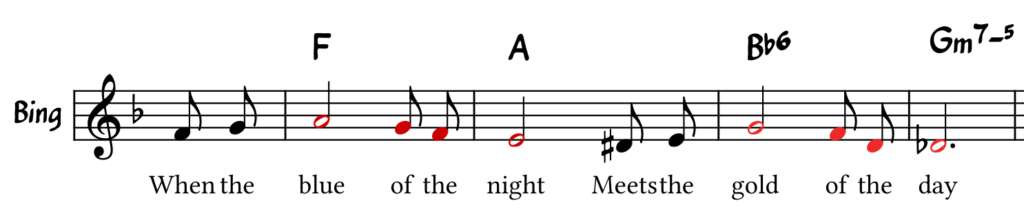

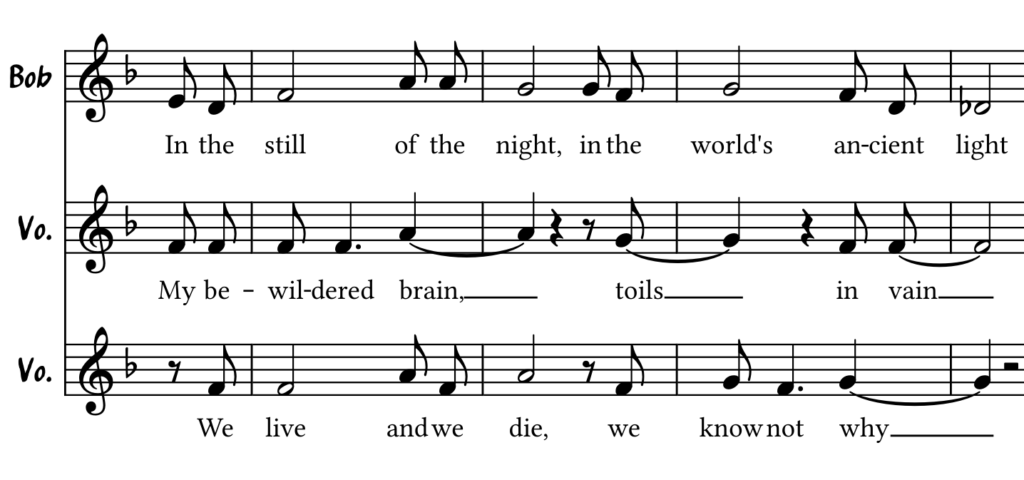

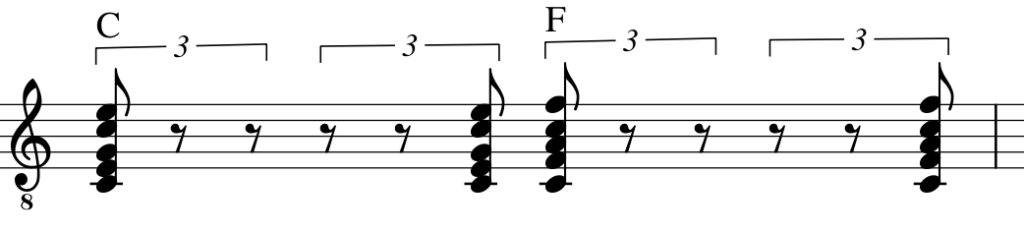

It is interesting because on the face of it, there is hardly any discussion: Dylan has stolen Bing’s song. Below are the two melodies. The chords are virtually identical, and so is the arrangement, so no need to discuss those. Here’s Bing’s version (top) and Bob’s (bottom):

Sure enough, a reviewer hell-bent on proving that Dylan is a plagiarist would point out that although the melody line in the beginning of the verses (“When the blue of the night meets the gold of the day”/“In the still of the night, in the world’s ancient light”) is not copied exactly, the melody at that point is not very distinctive in any case, in any of the versions – it merely consists of the main tones of the main chords (f and a, followed by e and g, respectively) and simple stepwise motion between them to fill the gaps:

Further, that as soon as some distinctive turn occurs, harmonically or melodically, such as the d flat, which lies quite far from the tone material of the key the song is in, at “day/light” in the fourth bar of the example, and the equally distinctive end of the line (“someone waits for me”) – Dylan follows Bing Crosby to the note:

The second and fourth line are repetitions of the first. In the third line, every note in the melody appears in exactly the same sequence as in Crosby’s version. So again: evidently, Dylan has just stolen Bing’s song:

Or has he? How would a more apologetic reviewer characterize these similarities?

Have a look at Bing’s initial phrase again:

The phrase is shaped so that the descending fourths a-e and g-db are emphasised. Rhythmically, it’s a constant ti-ti-taaa, ti-ti-taaa, giving a certain nightly calm, and again emphasising the endpoints. One might also see the end of the phrase as an echo going in the other direction (ta-tiiii, ta-tiiii, taaaa):

Compare this to Dylan’s three different renditions of the first phrase:

Several things are clear: the distinctive d flat appears in the first phrase, never to be heard again; the phrase is never sung the same way twice; the clear structure in Bing’s version is gone, replaced by variations over a skeleton consisting of the tones f–a–g–f, in that order, but realised differently every time.

It is interesting to note just how differently. This is one of the things that has fascinated me most about Dylan’s phrasing and singing style: how he manages to pick tones that both sound random and at the same time completely regular (only not, perhaps, according to any common rules). If you try to mimic it or copy it, it is actually quite hard sometimes, but once you put it on paper, it just looks banal – so banal that you look like an idiot who didn’t see it right away. He stays within – or rather: relates to – a certain framework, but can end up in very unusual places. See for example how the phrase above ends on three different notes – d flat, f, and a – and we still perceive it as the same phrase, somehow.

Which is also why the comparison with Bing Crosby’s version is so interesting: hearing the two tracks side by side, it is obvious that Dylan’s song is “based on the melody from a Bing Crosby song” – it’s as if Bob is singing harmony with Bing – but note for note it is most of the time difficult to find direct identity between the melody lines.

With the third line it’s the other way around: note for note the two versions are identical, but the character of the result is quite different. Bing slows down the rhythm, from repeated ti-ti-taaas to an even more contemplative ta ta- taaaa, taaaa, ta ta-taaaa (“If onlyyyyy aaaai could seeyouuuu”). Dylan, on the other hand, has more on his mind and turns the two-phrase line into three dense lines of text, thus making this phrase conform with the metrics of the rest of the stanza.

So although the melodic outline is identical, the character is very different. This is why, at the time Modern Times came out, I wrote:

We now know the answer to the last question [i.e. how similar they sound]: Not much, actually. Although the song structure and he chords are identical, the phrasing, the melody line, and the pace in Dylan’s version are all very different from Crosby’s slow, insinuating crooning. It is indeed “a song based on the melody” from “Where the Blue of the Night” rather than “Where the Blue of the Night” with new lyrics.

The last part is the crucial one: in some sense, When the Deal Goes Down, is precisely that: a song, to some extent new, although based on Where the Blue. There is some creative input in it, there are clear traces of Dylan’s very own phrasing, it is distinctively Dylan and no longer just a new set of lyrics to a stolen melody.

That is what the friendly, apologetic reviewer would argue. One thing is missing from his argument, though: it is still not a Dylan song, and to call it so is very wrong – factually, and probably also morally. It’s Dylan’s cover of Crosby’s song, sung to his own new lyrics. But musically it’s still a cover.

Exhibit F: We Three

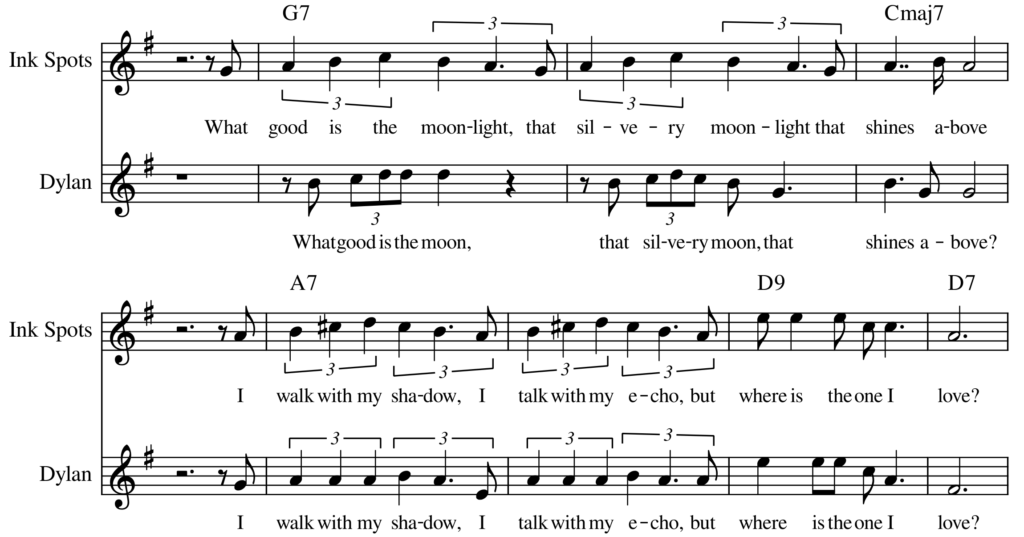

In this respect, it strongly resembles the way Dylan has always been covering songs (at least since the 80s). Many of the same strategies can be found, e.g., in his version of We Three (My Echo, My Shadow, and Me) from 1984, probably based on the 1940 recording by The Ink Spots; it was the first recording of the song, and Dylan has played this particular version on his Theme Time Radio show.

The entire song makes for an interesting comparison, but here the middle eight gives us enough material to work with:

The original version has a mellowly meandering melody that circles around the main tones of the chords, but with equal emphasis on the harmonically zazzy non-chordal tones (a, c during the G block, a and b for the C part – e.g. no chord tones at all; A7 is repeated, and for the final D9 they both use the notes of the extended D chord). So: melodically and rhythmically regular and repetitive, harmonically slightly more advanced.

Dylan goes the other way around. The harmonic finesse is virtually gone – he mostly sticks to the tones of the basic triads, most clearly during the A7-part, which is reduced to a recitation on the keynote a, the one tone that is hardly touched upon by the Ink Spots.

What we get in return is a much more varied melody, underpinned by constantly changing rhythms: instead of a simple transposed repetition (G7->C, A7->D) we get two quite different phrases, made different not least through the different rhythmic shape of the two phrases.

In sum: Just as in the case of the Bing song, it is as if Dylan is improvising freely over the original, singing harmony with it (most clearly seen in the end of the music example, where he basically sings in parallel thirds with the Ink Spots). The techniques that Dylan has been working with when writing “a song based on a Crosby song” are quite recognizable as the techniques he uses here, when he is working on a cover version. The only difference in this case is the new lyrics.

This brings us, at last, to the first of the two test questions I announced in the introduction. The question “Is it plagiarism?” can be phrased in many ways, the juridical and the moral being the most common. But a better starting point (unless you’re an attorney or being ripped off) might be to ask instead: “Why would I listen to Dylan’s version instead of the original?”, in other words: to make it an aesthetic question.

In the case of We Three the answer might be: because of the artistic input that shines through in the way he transforms the melody. In the case of When the Deal/Where the Blue, we also get Dylan’s new lyrics. In both cases, we get something from Dylan’s version that we don’t get from the original.

And still.

While our detour through the comparison with Dylan’s cover song technique may show that there is substantial artistic value in his reworkings, it is still not Dylan’s composition; a “Written by Bob Dylan” label is not justified.

So Bob: It’s OK to play covers. Just say so.

Exhibit G: False Prophet but True Crime?

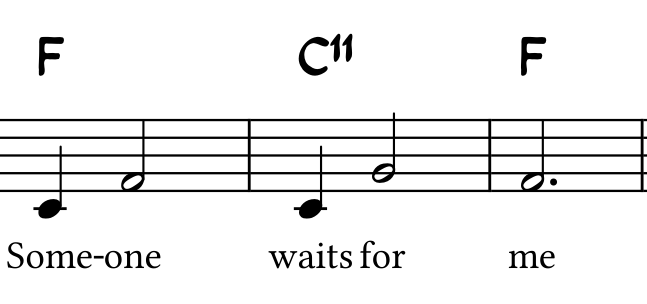

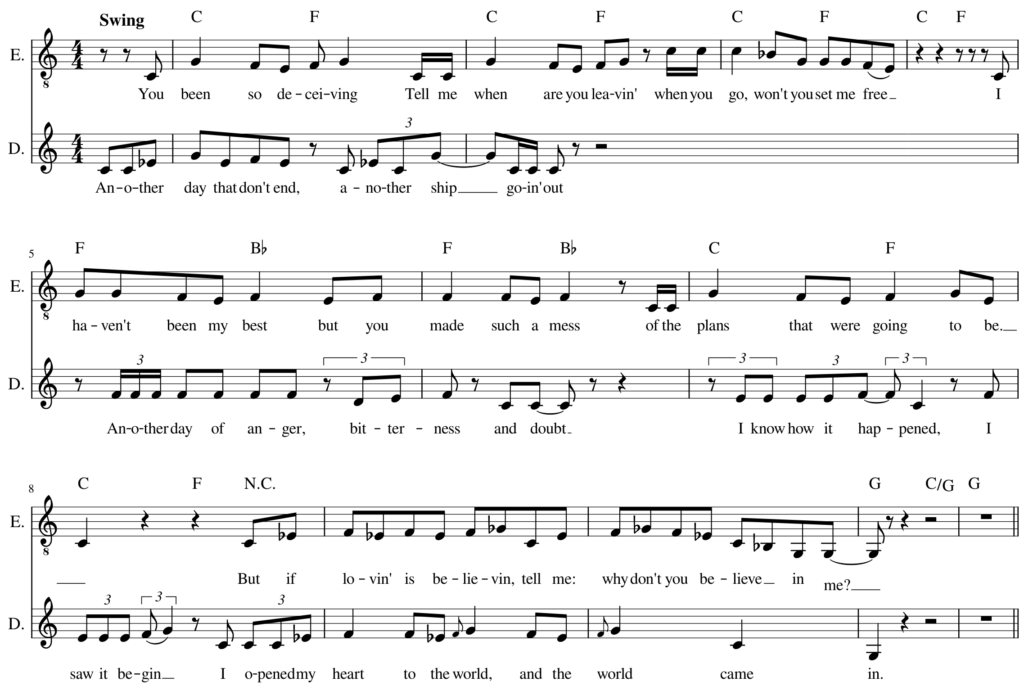

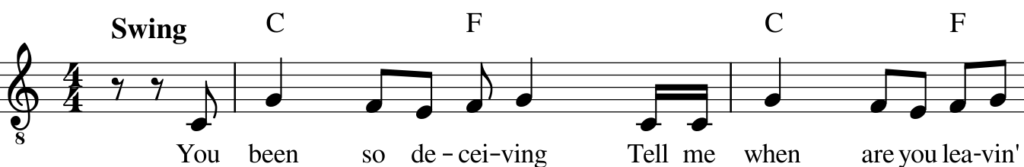

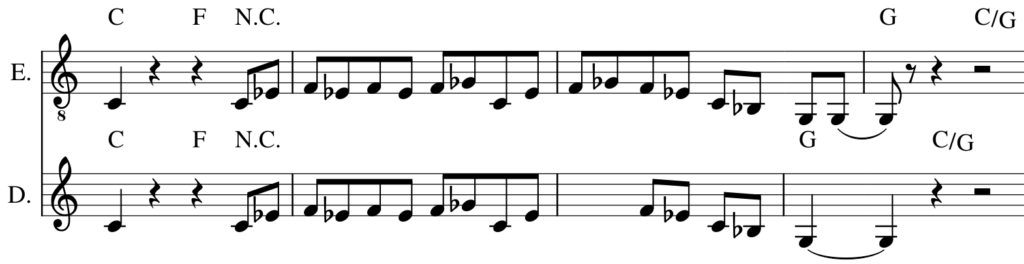

Which finally brings us back to False Prophet. Here is the first verse of Billy The Kid Emerson’s version (top) and Dylan’s version (bottom):

With the previous examples in mind, it is easy to recognize the picture: Dylan’s melody line is hardly ever exactly like Emerson’s, but it follows it like a harmonizing second voice, or as an improvisation over the same outline. The tendency to stick to the notes of the triads and avoid harmonic subtleties that we have discussed earlier, is clearly recognizable even here.

See for example the difference between the first two phrases: in the first, Emerson’s melody emphasises the tones of a C chord (with the characteristic bluesy ambiguity between major and minor):

Dylan sticks even closer to these tones and mostly avoids Emerson’s melody, which is nevertheless recognizable both in the overall flow of the phrases and in fragments here and there, such as the descent g-f-e in the first measure and the c-g skip in the beginning and at “tell me when/(ano)ther ship”:

In the second phrase, the harmony changes from C to F. Emerson simply repeats the melody with the same tones, thus creating some kind of bitonality – the implied C of the melody line against the F of the accompaniment. Dylan instead avoids this complexity and emphasises the new key by reciting on an f.

This is familiar: this is how Dylan sings covers. So what about the rest of the song?

Here’s what: The recurring riff is copied note for note almost without a change, but also with regards to the sound: the distorted guitar and the parallel melody line in different octaves. The tempo is exactly the same (78.5 bpm) and the swing ratio is indistinguishable (slightly less than 2:1; Emerson maybe closer to a straight 2:1, but it’s hard to tell).

Two things have changed: The riff has been shortened by two beats, and the verse skips two bars. In one of the apologetic texts I link to above, these two changes are elevated to a gigantic artistic effort: “It transforms something standard, a form we’ve heard forever, into something ear-catchingly new.” This is stretching it quite a bit (in the first version of this text, I wrote: “Bullshit”). The changes to the blues pattern itself, up until the riff, could just as well be described as “normalizing” rather than “ear-catchingly new”. At the heart of the song is the rhytmic figure that runs through the whole song (apart from during the main riff, where the accompaniment falls silent):

Repeat this, and we have the two-bar block that is the main structural element of the verses. In Emerson’s version, this block is repeated on the I step, followed by one block on IV and one more on I, whereas Dylan leaves out the first repetition, resulting in three identical blocks on I, IV, and I, respectively:

Emerson:

I . | . . | . . | . . |

IV . | . . |

I . | . . |

Dylan:

I . | . . |

IV . | . . |

I . | . . |

In the riff, two tones are left out, bringing the whole passage down from eight to six beats:

Again, this can hardly be called earth-shatteringly new. In Emerson’s case, the riff already brings a radical change in rhythmic character from the distinctive “chop . . . chop-chop” of the rhythm guitar. Dylan adds one small element of irregularity (but removes the slightly syncopated final tone of the phrase). Billy Emerson’s original is already a somewhat irregular version of the 12-bar blues which happens to fill 12 bars in the end.

Dylan and his band copy everything: sound, rhythm, phrasing, key, tempo, swing, chord structure, adding nothing of substance, other than what Dylan always does when he sings. If it wasn’t for the lyrics and Dylan’s vocal idiosyncracies, and the specifics of the recording session, it would be difficult to tell Dylan’s version apart from the original. (As an aside, I’m slightly puzzled by the willingness with which the apologetes accept Led Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love and Harrison’s My Sweet Lord as obvious cases of plagiarism, although it would be easy to argue that the changes in both those cases are more substantial than Dylan’s changes to If Lovin’, but I’ll leave that for a later text.)

This is where False Prophet and When the Deal differ: in When the Deal, the harmonic layer is varied enough to make Dylan’s new phrasing and changes to the melody line an interesting counterpoint to the original. In False Prophet, on the other hand, the basic structure and the harmonic foundation is so plain – two main chords, one rhythmic pattern – that if singing style is the only thing that sets the two versions apart, it really is hard to tell which is which.

And this leads me to my second test question: If I were to write my own rip-off, with new lyrics, of either of the songs, Dylan’s or Emerson’s, would you be able to tell the difference? Which song had I stolen? Whose lawyers would come after me – Dylan’s or Emerson’s?

Closing Argument

It is quite unclear to me what we should call the art form that Dylan is excelling in here. It’s not a cover song. But it’s not not a cover song either. It may come close to sampling, but it’s not. Dylan’s song would probably never have seen the light of day if Emerson hadn’t recorded it three score and six years ago, but in the form Dylan has given it, there is a long way back to its origins.

That is, again: if we except the chord structure, the riff, the sound – everyhing but the vocal delivery and the lyrics.

One of the articles dealing apologetically with the thefts – this time concerning Dylan’s Nobel Prize Lecture and how large chunks of it is taken from one of those sites where students go to cheat on their exams so that they won’t have to read all that boring stuff on the curriculum – sums up the relevant question already in the title of the piece: “Does it matter if Dylan copies other people’s words and melodies?”

Does it matter? And if so: why?

The author goes on to distinguish between moral and legal matters, which is also interesting, but more critical is this: if a student cheats by going to one of those websites, it’s probably either because he doesn’t care or he doesn’t have anything to say. So why should we listen to someone like that? In the academic world, the way to respond in such a case is to fail the student. In the world in general, well, why would you listen to someone with nothing to say, who by the way couldn’t care less?

It is only in the artistic world that such behaviour can somehow be legitimized and justified: it’s a statement, it’s a meta thing, a reflection on the act of communication and what not.

Bullshit. It’s lazy and sloppy, it’s completely unnecessary, it may or may not be illegal and wrong, it may or may not be greedy, but in any case it’s disrespectful, towards Emerson and towards me as a listener, so why should I pay it any mind (or for that matter: money)?

I hate to admit it, and I refuse to close my eyes on the legal, moral, and aesthetical problems with Dylan’s version, and I had intended a much more damning closing salvo, but maybe this is why:

There is no doubt (in my mind, at least) that Dylan’s song is infinitely better than Emerson’s.