Note entry by keyboard is usually highly inefficient in score editing programs, and MuseScore is no exception.

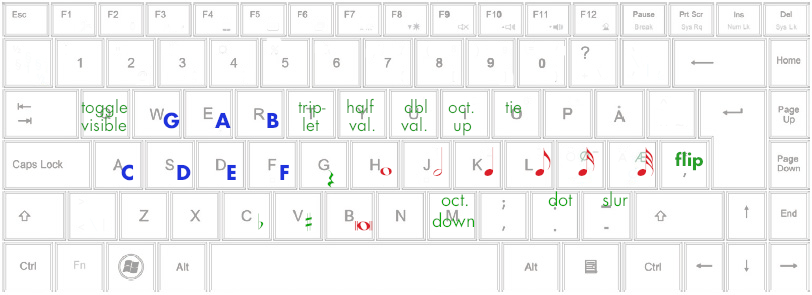

By default, notes are entered with the corresponding letter keys (c=c, d=d, etc.), whose placement on the keyboard does no follow any muscial logic. Incidentally, all the note names are placed on the left-hand side of the keyboard, but in no systematic order. The rhythmic values are typed in with the number keys, way up on the top line of the keyboard. This means that all the keys you would use for inputting music happen to lie on the left-hand side, so even if you’re an exceptionally skilled typist, entering music is unnecessarily slow, since you would end up jumping around senselessly with your the left hand:

My Way

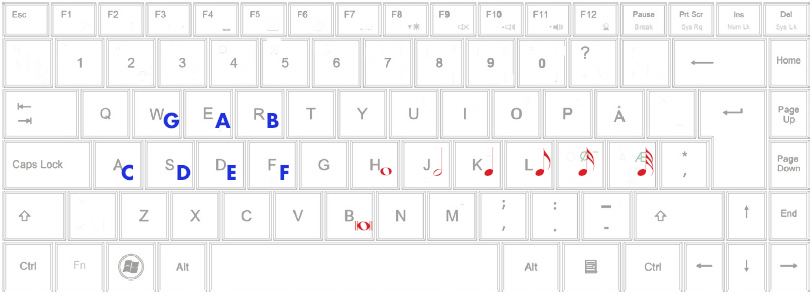

I use a different layout, which makes it possible to “play” on the keyboard more like a piano keyboard, all on the home row or the adjacent rows. No jumping around.

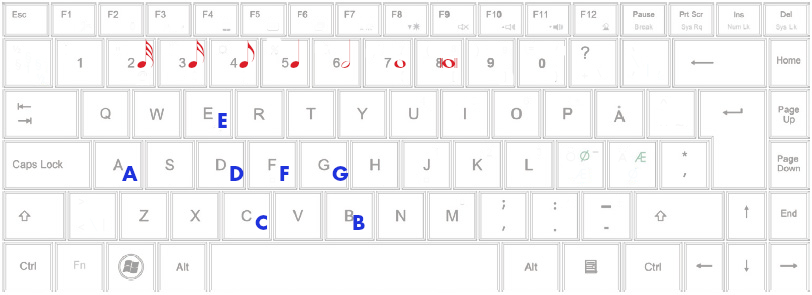

Note entry is done with the left hand, rhythms with the right:

The layout is based on the principle that music frequently moves by step, so having adjacent notes next to each other is a good thing. Also, fourths are common, so it is not unnatural to have d and g on the same finger.

The remapping therefore follows the scale and disregards the ordinary letters on the keys.

Similarly, rhythmic changes more often than not go to adjacent values, and the most frequent values are placed at the main positions of the hand.

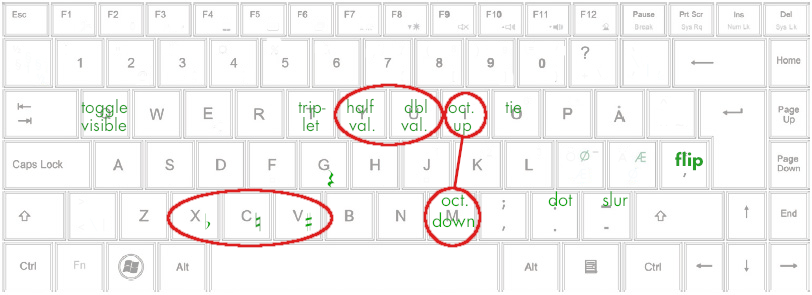

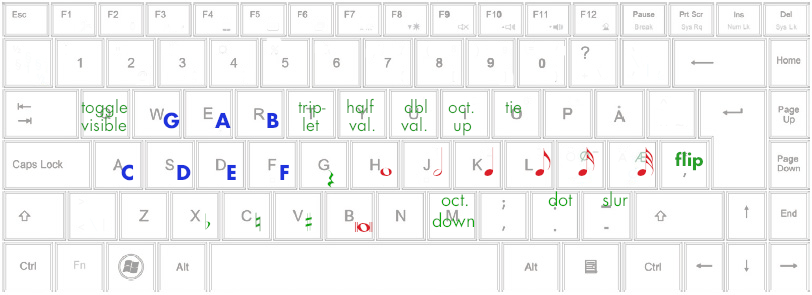

The remaining keys are mapped to common functions: rest (g, next to the notes), triplet (t), double/half time (y, u), octave up/down (i,m), flat/natural/sharp (x,c,v), dot (.), tie/slur (o,-); “q” (quiet) for “Toggle visible”:

All in all: a complete keyboard layout that is optimal for note input:

There are other shortcuts as well, which have nothing to do with the input system itself, so I won’t go into them. See the config files below for details.

What remains?

Thanks for asking. There are a couple of features that I would have liked to implement, which are not possible (yet!) because of missing keyboard shortcuts in MuseScore’s current layout, as well as bad application choices more fundamentally.

I would e.g. have loved to have a key for “input dynamic” (e.g. p for “mezzo piano”), and then increase or decrease the value, going stepwise through the dynamics (so that repeated presses would go through p, pp, ppp etc. in one direction and mf, ff, fff, etc. in the other).

Likewise, it would have been great to be able to cycle through the accidentals within the currently selected pitch (so: a double-flat, a flat, a, a sharp, a double-sharp), rather than having Musescore decide/guess for you whether you want a a flat or a g sharp, or even worse: an a double-flat or an f double-sharp.

Downloads

Here are my keyboard shortcuts. To try them out, save the file, then go to Edit > Preferences > Shortcuts > Load …. and select the file that you downloaded.

Note that these files are based on the Norwegian keyboard layout. Adjust the keys in the rightmost area of the keyboard according to your own keyboard.