One surprising aspect of Bob Dylan’s music making is his way of handling dominant connections. Or rather: his way of not handling them – by consistently avoiding them.

In the following I will suggest how he avoids the dominant, how he uses it when he does not avoid it, and why he treats it the way he does.

How to avoid

The most common cliché about Dylan – apart from the self-evident truth that he can’t sing – is probably that he only uses three chords, i.e. , the chords on the scale steps I, IV, and V, the classical Tonic, Subdominant, and Dominant (in the following abbreviated T, S, and D). This is not entirely correct, but not entirely untrue either: Dylan is not a sophisticated harmonicist – he mostly sticks to the main chord functions.

This is partly to do with his general predilection for genres based on blues and ballad, where the main functions have a central position.

This makes it even more remarkable that Dylan, out of this already meagre selection of chords, tends to avoid one of the three. And when he does use dominant chords it is almost always in the plain, triadic version, rarely using the opportunity to heighten harmonic tension that an added seventh would provide. Dominant seventh chords are rare in Dylan’s production.

I consider these two avoidances – of the dominant and of seventh chords – as two sides of the same coin, and when I talk about Dylan’s avoiding the dominant, it is more generally about avoiding the dominant function, whether in the broader sense of a major chord on the fifth scale step with a certain position in an habituated chord pattern, or more specifically: as the build-up to the tonic towards the end of a phrase.

Simple Twist of Fate

Simple Twist of Fate is a good example to start with. A number of different live versions can illustrate the role of the dominant.

On the live album Budokan (1978) the end of the verse sounds like this:

C F

and wished that he'd gone straight

C F G C

And watched out for a simple twist of fate.

In other words: a very classical tonal cadence of the most unremarkable form: T-S-D-T (C-F-G-C).

But in the original version from 1974, the ending goes like this:

E B/d# A

and wished that he'd gone straight

E B11 E

And watched out for a simple twist of fate.

What used to be the S-D part of the cadential figure (at “simple twist”) is reduced to an eleventh chord, a chord that is essentially a subdominant chord with only the bass tone left from the dominant.

This is a severe weakening of the dominant character of the chord: no leading notes left (i.e. the halfstep relation, which draws two chords together like a magnet), no T-S-D-T cadence progression, no sharp contrast between two different tonal areas, but instead a step in the progression which already contains the note of resolution, the tonic: instead of the leading note resolution D#–E, we have a penultimate chord that already contains E.

Between these two version lies the 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue tour, where the same passage sounds like this:

G D C

and wished that he'd gone straight

G Am G

And watched out for a simple twist of fate.

The dominant is gone altogether! It is replaced not even by a subdominant, but by the subdominant relative minor. One can hardly get farther away from a tonal cadence (whereas it has certain modal traits).

In sum: The main part of the verse moves in the I-IV area and the melodic and emotional climax of the melody lies on the IV step, on “gone straight”. The dominant step on the other hand – to the extent that it is used at all, and regardless of how it is avoided – is merely an afterthought, a sidestep after the climax, after the tonic has been reached, far from the traditional dominant function.

Ballad of a Thin Man

To this trio of versions of a song can be added other songs where other strategies are employed. Ballad of a Thin Man (off Highway 61 Revisited, 1965) is our first example. On two points in the song there is an obvious opportunity to heighten the tension and drive towards the tonic through a stronger exploitation of the dominant function, but this opportunity is not taken advantage of.

The verses are mostly built over a chromatic descent in the bass:

Am

You walk into the room

/g#

With your pencil in your hand

/g

You see somebody naked

/f#

And you say, "Who is that man?"

F

You try so hard

Dm

But you don't understand

At the end of the descent comes the first marked return to the tonic:

C Em Am Just what you will say When you get home

It would not be inconceiveable with a major dominant chord here, but that never happens, not in a single live version through the years. On the contrary: in most live arrangements the entire phrase from “Just what …” is sung to a static riff on the tonic, without the slightest hint at the possibility of a dominant turn:

Am Dm/f Am

what you're gonna say

Am Dm/f Am (=intro figure)

When you get home

The other point worth mentioning in this song is the transition from the bridge to the verse. The bridge ends with a strongly emphasised and outstretched G major chord (dP), the relative major of the dominant, before the return to the Am of the following verse.

Dm G ( --> Am ) tax-deductible charity organizations

This is the climax of the song, in terms of pitch and volume. Again, it would not be inconceivable with a chromatic bass ascent g-g#-a to tie the two parts together through the hint of a first inversion dominant chord (G – E/g# – Am). This variant actually does occur, during the 1984 tour:

Dm G . . . E/g# ( --> Am) To tax-deductible charity organizations

But in the absolute majority of the cases, this opportunity to create harmonic tension is left untouched.

Open Tunings and the Gospel Idiom

The previously mentioned album veresion of Simple Twist of Fate represents a specific strategy to avoid the dominant function, which appears from two different angles during the seventies.

The first stems from the album Blood on the Tracks, recorded in 1974, where the song first appeared.

In its first version, the entire album was recorded i open E tuning. In open E, the guitar is tuned to an E major chord, and while it is of course possible to play a straight dominant chord (most simply by playing a full one-finger barre chord at the seventh fret), it is not common, since one of the points of open tunings in the first place is to take advantage of the open strings as drone-like tones. Thus, if the top E string is left ringing with the B chord, it will in practice produce a B11, i.e. a subdominant with the bass note of the dominant, as we saw it in the music example above.

Thus, the eleventh chord, which fits his general reluctance towards the dominant function like a glove, was introduced in Dylan’s music thanks to the guitar technical experimenting with open tunings that he was engaged with at the time. But when it stayed in his idiom, it was thanks to the gospel tradition that Dylan dived into when he turned born-again christian in 1978. Here, it is one of the most characteristic chords, and after 1978 the eleventh is a fairly frequent variant for the dominant in Dylan’s songs – that is: a dominant that isn’t quite one.

Dominating the Blues

A large part of Dylan’s songs are based on the blues, in some form or another. In this area, the avoidance of the dominant is not so much a matter of avoiding a specific chord – most of Dylan’s blues based songs do after all contain the chord on the fifth scale step – but about Dylan’s way of relating to fixed chord progressions where specific chords have specific roles and functions.

So while it is certainly interesting that Dylan’s catalogue contains blues songs with no dominant chord whatsoever – e.g. Tombstone Blues – this is less significant than the myriad of variants of the “Twelve Bar Blues” that he uses throughout his career, and the general tendencies that can be gleaned from this material.

Here is the twelve bar blues as we know it and love (to hate) it from all the pub bands and stadium rock classics of the world:

I IV I I7 IV . I . V IV I V7 (turnaround)

Dylan quite consistently changes this pattern in various ways:

1. He lets the first part of the pattern, where the accompaniment lies on I, last for the entire first four-bar segment:

I . . . IV . I . V IV I V7 (turnaround)

2. He also tends to avoid the otherwise so characteristic V-IV-I-turn towards the end, and instead replace it with a single V over the whole first part of the third line (The similar I-IV-I turn in the first line has already disappeared in the first reduction):

I . . . IV . I . V . I V7 (turnaround)

3. He is not a big fan of turnarounds. They do exist, but not very frequently:

I . . . IV . I . V . I .

This, then, is the blues pattern most frequently found in Dylan’s production, in this exact form or in one of the many variants in terms of phrase length, irregular rhythmic patterns, etc.

In addition to these concrete observations, some further tendencies can be noted:

- A predilection for the treatment of the T-S connection, whereas D seems to be used as a more dutiful step.

- He seems to like long, static stages; for example, his preferred version of the sixteen-bar blues is to stretch the initial T step to twice its length, and his reductions 2 and 3 also work to prolong even the other steps into entire stages, at the cost of the dynamic drive that harmonic variation provides.

- The range of variation between his different versions within the simple blues pattern is astonishing.

Standing in the Doorway

These tendencies or preferences are not limitied to his folk period in the sixties. The same characteristics can be noticed e.g. in Standing in the Doorway from 1997.

In a way it is a blues song: most of the verse is a statically repeated descending bass line, e-d#-c#-b, which functions as a stretched-out tonic.

It is followed by a passage around A, corresponding to the turn to the Subdominant in the blues pattern, after which we return to the tonic E again for yet another round of the static bass line.

In the place where the dominant would appear, corresponding to the beginning of the third line in the twelve-bar blues pattern, we then have the quick sequence A-E-B-F#-A-E, in other words: a chain of fifth-related chords, giving the impression of a dominantic circle progression since the chords become more and more “dominantic” in the sense that they get more and more sharps, but in this case the chain actually moves in the subdominant direction. Thus, it is not a constant discharge of an established level of tension, but a tentative “subdominantic persistency”, which ends on the secondary dominant, F#, which, however – possibly because of some minor variant somewhere in the mix, or because of associations (established thanks, in part, to the emphasis on the subdominant throughout the song) – is perceived more like the major variant of the minor relative of the subdominant, F#m.

In sum: after the long standstill on the tonic, we get a gesture that produces an illusion of a dominantic circle progression, but in the wrong direction and where the goal of the harmonic progression is not the Dominant in preparation of the return to the Tonic, but instead the Subdominant.

The Dominant, B, is a part of the progression, but its role is very modest: it is simple one element in the chain of chords that leads to F#:

A E B F# You left me standing in the doorway crying A E I got nothing to go back to now.

How Not to avoid the Dominant?

As an illustrative contrast, it may also be worth looking at the cases where Dylan actually uses shamelessly dominantic turns and/or seventh chords. I shall suggest three areas:

1. Even though Dylan is disinclined to emphasise the dominant in his own blues songs, he gladly uses them as a genre marker. The most obvious example is Rainy Day Women #12&35 off Blonde on Blonde (1965), an almost-parody of an unrestrained New Orleans brass blues; but also the jazz pastiche If Dogs Run Free (1970) and various genre exercises from the country oriented albums from the late sixties fall in this category. What they have in common is the mimicking tone – as if he doesn’t really mean it completely earnestly.

2. Covers. When Dylan plays other artists’ songs, he is usually faithful to the original, also on this point. This is not least apparent in the series of Sinatra inspired albums starting with Christmas in the Heart (2009). Song upon song are overflowing with dominant circle progressions, performed with conviction and gusto, and no sign of shame.

3. But the most revealing group of cases are those that stem from guitar tuning and preconditions based on key. These are revealing precisely because they indicate that not only does Dylan happen not to play dominant seventh chords: he actually actively avoids them.

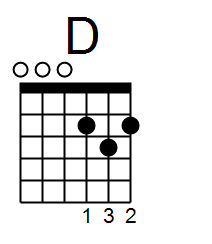

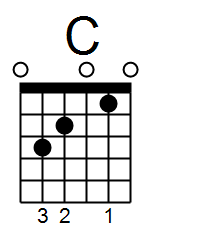

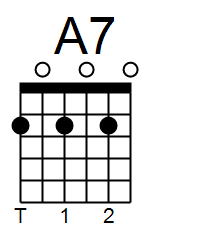

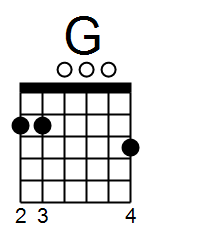

Two alternate tunings that Dylan used consistently during the sixties are called “Drop D” and “Drop C”. Here, the sixth string is tuned down one and two whole steps, respectively. In Drop D we have the three following main chords:

The main connection in this tuning is between I and IV (D and G): they share open strings and fixed fingers (the ring finger stays in the same place, and the index finger moves a short distance) – they stand in a close relation both on the fretboard and in sound. The dominant, on the other hand, is slightly awkward, which can be heard, especially when Dylan plays it: it calls for bigger hand movements and tends to sound muffled – it is difficult to get the first string to sound properly. In this tuning, the Dominant does not fulfill its potential to stand out as the bright, contrasting contender.

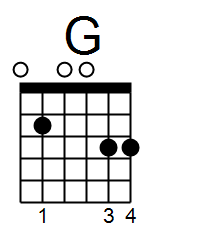

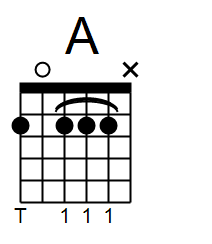

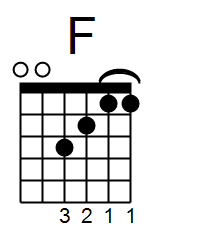

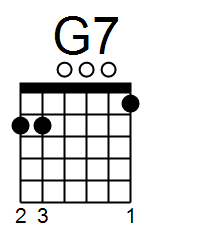

In Drop C, the way Dylan plays it, these are the basic chords:

Here, too, there is a close and natural relationship between I and IV (C and F), in terms of fingering, but in this tuning even the V chord, G7, is an unhampered part of the group. Both the S and D chords relate to the tonic chord according to the principle “least possible movement”, of which Dylan is a masterful proponent.

What is most interesting, however, is that the songs Dylan plays in Drop C are among the very few songs in his entire production where the dominant seventh is consistently used. Here is the version of It’s All Over Now Baby Blue from Live 1966:

E F G7

Look out the saints are comin' through

Dm F C

And it's all over now, Baby Blue.

The alternatives to the two dominant chord shapes in these two tunings are worth a comparison:

In Drop D it would be possible to replace the muffled and awkward A with the A7 shown here if one wanted to. Soundwise it would definitely be preferrable – it would be easier to play and to use all strings to their full potential. But Dylan evidently risks a slightly bad sound rather than including the unwanted seventh.

But in Drop C, the risk involved in playing the straight G is apparently too big. It is possible to play it the way that is shown here, but it involves some acrobatics in the movements of ring- and little fingers, which one cannot allow oneself in a practical live situation where one stands alone with the guitar as sole responsible for the accompaniment. In such an extreme situation, Dylan permits the Dominant seventh, but that is how far out we have to go. That’s how much he seems to distrust this chord.

The difference between the chord shapes in Drop D and Drop C, then, is a strong indication that Dylan prefers the straight dominant to the heightened harmonic tension of the seventh.

One last example in this area might be mentioned: Dylan remarkably rarely plays in E major, even though that is one of the most common keys to play in in the genres that Dylan enjoys. There may be many reasons for this, but it could be a contributing factor that it is more difficult in E major than in many other keys to find suitable chord shapes to avoid the dominant seventh.

Why?

So why this resistance to dominant chords?

Early Country Blues and English Ballads

One explanation that lies close at hand is that in the music that is Dylan’s bible, the dominant function is not important. This goes for the early blues as well as for the English ballad tradition.

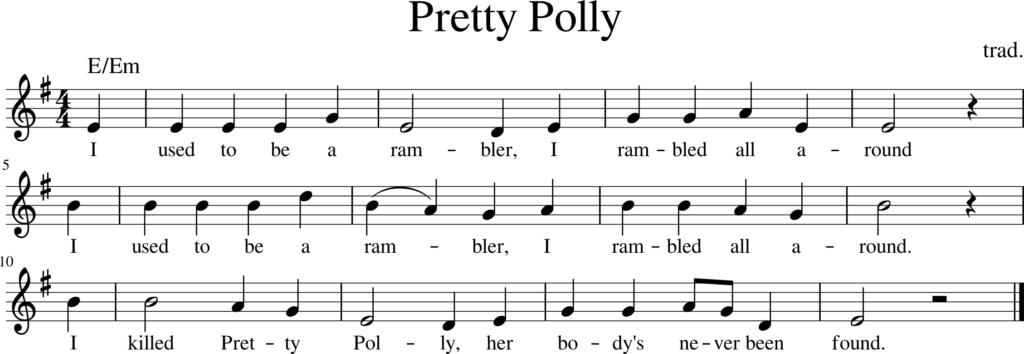

In the early blues that Dylan soaked himself in early in his career, the dominants are generally few and far between, and it is not a coincidence that Dylan bases several of his songs in part or in full on the Pretty Polly pattern, where a pentatonic phrase is played around the first scale step, then repeated around the fifth, and rounded off with a return to the tonic again – often played without differentiation in the harmonic accompaniment:

The fifth scale step represents an alternate tone area, but does not have the function of harmonic tension that it has in a harmonic progression.

The simple version of the blues pattern that Dylan prefers, without V-IV turns and turnarounds, comes the closest to the Pretty Polly pattern: the chords are static layers, around which melodies and instrumental figures can move relatively freely.

The Anti-Harmonical Dylan

What the examples above seem to indicate in a more general sense, is that in Dylan’s music it is not harmony that rules the musical progression – it is the voice (partly, but not just, as carrier of the text) and the phrasing. The long stages on static levels are far more open to variations – spontaneous as well as planned, as in language – than the pre-defined steps of the established harmonic patterns of tonal harmony.

And this seems to be a very conscious choice.

I have elsewhere argued that what Dylan does – although he “can’t sing” and “only knows three chords” – is to make prose music: he treats the obviously stylized and strongly regulated world of sound that musical expression necessarily is, as if it were equivalent to the sound world that language is when it does not appear in poetic form – that is: in the form with a level of stylization that is equivalent to what music usually is.

He explores the common grounds between language and music, in other words. That is the art form that in which he excels: the exploration of the conection between the sonourous qualities of language and the quasi-conceptual qualities of music. He pretends that it is possible to talk in prose through and within music’s poetic world of rhythm patterns and established harmonic progressions.

And in this framework, there is no obvious place for the dominant, since it, by being a purely musical mode of expression cannot be “proseified” so to speak: pure harmony is the one element of music that lacks a direct equivalent i language (the idea of several voices at the same time, which is the foundation of harmony, in the area of language more than anything evokes images of quarreling or power games). And the dominant is a pure representative of this: there is no linguistic correspondence to or element in the seventh chord.

But if the dominant is instead reduced to a static stage without necessary consequences (such as: the tonic), it can still be drawn into the Dylanic art form.

A corollary of this argument is that Dylan is not a literary artist (and hence it was a mistake to give him the Nobel prize), nor is he solely a musician (and hence it was a mistake to put him through the ordeal that was the Polar prize) – he is a prose singer, and in prose, the dominant has no obvious place.

First presented as a paper at the annual conference of the Swedish Musicological Society in 2018